_1972.jpg) |

| Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants) - 1972 |

Ana Mendieta (1948 – 1985) was a well-rounded Cuban artist who used a

variety of mediums which included painting, sculpting, video and performance.

She is most well-known for her theatrical performances and displays that

combined the themes of ethnicity, gender, nature and death in ways that were

never before explored. Mendieta was a Cuban exile forced to flee her home

country at 12 years old to escape Fidel Castro’s threatening rise to power.

From Cuba, she was transported to Iowa where she begun to explore her

relationship with her Afro-Caribbean roots after being fully brought up and

socialized by Midwestern American culture. Under the teachings of Hans Breder,

she obtained her MFA in Intermedia Studies and focused almost solely on the

performance art she is recognized for.

|

| Tree of Life - 1976 |

|

| Silueta Series - 1973 - 1980 |

Undeniably Mendieta’s most famous work, Silueta Series (1973 – 1980), fits wonderfully within one of the main aspects of 1970s feminism which sought the reclamation of the depiction of female bodies. Of this particular series, Chadwick explains, “Her [Mendieta’s] work made powerful identifications between the female body and the land in ways that annihilated the conventions of surface on which the traditions of Western art rest” (374). In what she deemed “earth-body work,” she made direct connections between Afro-Caribbean notions of Mother Nature and the naturalness of the female body, of which traditional Western art and culture considered vulgar and private. In a truly defiant technique, Mendieta used her own naked body to form many of the outlines for Silueta for a clear silhouette of the female form within the earth. During its creation, as well as now, the series has been criticized by males and feminists alike for its supposed sexualization of the female body, which feminists were fighting to wipe out. A critic of Mendieta’s work echoes this concern: “Mendieta’s essentialism can be characterized as a reliance upon an ahistorical idea, mother earth, to generate the Silueta Series. Thus the traditional link between the female body and nature is supported and a received idea about sexual difference is retained” (Susan Best, 57). Conservative males preyed off of these disagreements within the feminist community to demonstrate how dangerous a female in control of her own body can be.

|

| Venus Negra |

|

| Untitled (Rape Scene) - 1973 |

|

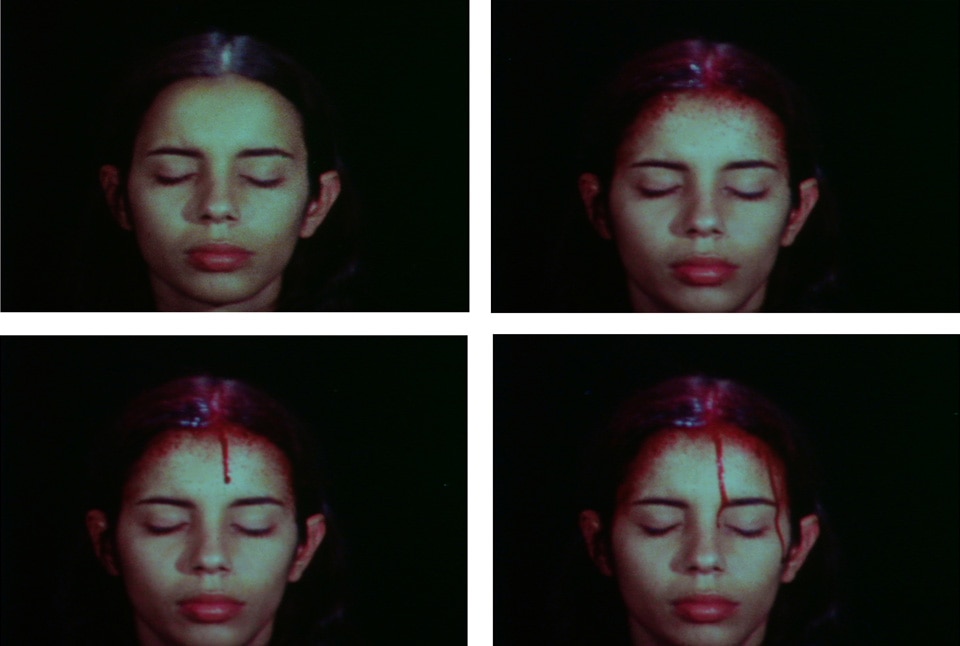

| Sweating Blood - 1973 |

Outside of Silueta, Mendieta

commonly used blood in her most dramatic performances. In one of her most

controversial works, Untitled (Rape

Scene), her bloodied and half-naked body was tied to a table and put on

display for her invitees. This performance is an example of a work that is not

art just simply for art’s sake, but a statement dealing with real-life

situations that objectify and degrade women and their bodies. About this work,

Cabañas poignantly

states, “She used it to emphasize the

societal conditions by which the female body is colonized as the object of male

desire and ravaged under masculine aggression…The audience was forced to

reflect on its responsibility; its empathy was elicited and translated to the

space of awareness in which sexual violence could be addressed” (12). The use

of blood is also present in Untitled

(Self-Portrait with Blood), Untitled

(Death of a Chicken) and Body Tracks and

has been understood to be connected with her exploration of Santería, a traditional religion

of the Caribbean. Her bloody performances like Sweating

Blood are

said to resemble practices that derive from the religion.

|

| Untitled (Body Tracks) - 1982 |

Although most of her work was

ephemeral, its influence lives on. Eleanor Heartney finds Mendieta’s influence

in the work of contemporary artists Janine Antoni and Tania Bruguera

in the ways in which they use their bodies to make statements about the female

condition (139). The cause of Ana Mendieta’s early death is still contested

today, but her death ironically symbolized the themes of degradation and

devaluation of female life that she and her contemporaries tackled in their

works. Mendieta’s use of a wide array of mediums and materials (blood, animals,

earth, etc.) expanded the meaning of performance art and brought women to

exhibit their work outside of discriminatory museums. Cabañas

says of Mendieta’s legacy, “She

positioned herself, a female and ethnic Other, as a subject and recognized the

contingency between the individual body and the social body; her art takes us

across the borders of individual and social, self and Other, subject and object”

(16).

Works

Cited

Best, Susan. "The Serial Spaces

of Ana Mendieta." Art History 30.1 (2007): 57-82.

Blocker, Jane. "Ana

Mendieta and the Politics of the Venus Negra." Cultural studies

12.1 (1998): 31-50.

Cabañas, Kaira M. "Ana

Mendieta:" Pain of Cuba, Body I Am"." Woman's Art Journal

(1999): 12-17.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 5th ed. New

York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1990. Print.

Heartney, Eleanor. "Rediscovering

Ana Mendieta." Art in America 92.10 (2004): 138-143.

No comments:

Post a Comment